Screening & Diagnosis of Cerebral Palsy

Diagnosing cerebral palsy (CP) at an early age is important for the long-term outcome of children and their families.

While cerebral palsy (CP) diagnoses have traditionally been made at 2 years of age or older, recent studies have shown that specialist providers can make the diagnosis as early as 6 months of age in some cases. International guidelines for early diagnosis and intervention for cerebral palsy were published in 2017.

Developed by a multidisciplinary group of scientific and clinical experts and parent stakeholders, these guidelines are based on the latest systematic review of the evidence. They state that early recognition of CP can and should occur as early as possible so that:

• The infant can receive diagnostic-specific early intervention and surveillance to optimize neuroplasticity and prevent complications

• The parents can receive psychological and financial support, if available

Diagnosing CP can include several steps including Developmental Monitoring, Developmental Screening, Developmental and Medical Evaluations.

WHAT ARE SOME OF THE BEST WAYS FOR A PEDIATRIC PROVIDER TO RECOGNIZE THE NEED FOR REFERRAL FOR EARLY CP EVALUATION?

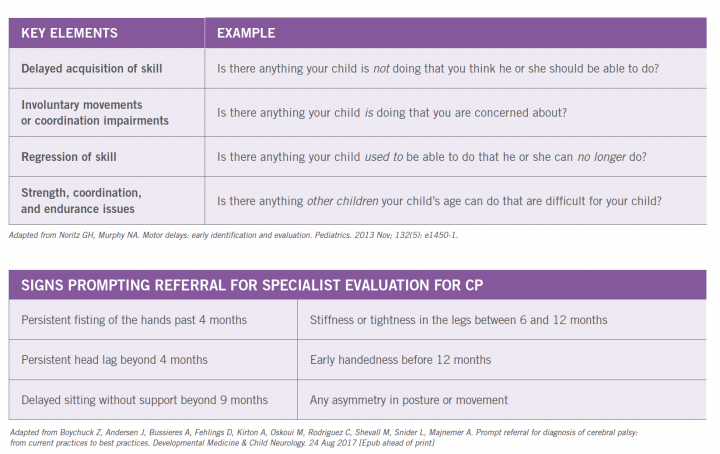

The international guidelines specify two primary types of very young patients who should be evaluated for cerebral palsy. Those with “newborn detectable risks” have clear risk factors identified before, during or soon after birth – these include children with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), neonatal encephalopathy and/or children born preterm. The second group has “infant detectable risks” which typically manifest after 5 months corrected age, most often to children who did not receive care in a neonatal intensive care unit. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends developmental surveillance at all preventive care visits and standardized developmental screening of all children at 9, 18, and 30 months. Primary care pediatric providers, as medical homes for children, can often identify infant detectable risks with the use of evaluation tools established by the American Academy of Pediatrics and expert consensus surveys. Notably, these tools involve asking questions of parents to learn key elements of motor history, and focusing on six agreed-upon signs that should prompt early referral to specialists for detailed evaluation of CP.

The components used for an early diagnosis include

- Clinical History

- Neurological exam

- Motor function assessments

- Neuroimaging

- Biomarkers

neuroimaging techniques

Neuroimaging techniques that allow doctors to look into the brain (such as an MRI scan) can detect abnormalities that indicate a potentially treatable movement disorder. Neuroimaging methods include:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT): uses x-rays to create images that show the structure of the brain and areas of damage

- Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI): uses a computer, a magnetic field, and radio waves to create an anatomical picture of the brain's tissues and structures. An MRI or DTI can show the type of damage and offers finer levels of details than CT. Some metabolic disorders can masquerade as CP. Most of the childhood metabolic disorders have characteristic brain abnormalities or malformations that will show up on an MRI.

- Electroencephalogram: another test that uses a series of electrodes that are either taped or temporarily pasted to the scalp to detect electrical activity in the brain. Changes in the normal electrical pattern may help to identify epilepsy.

- Cranial ultrasound: uses high-frequency sound waves to produce pictures of the brains of young babies. It is used for high-risk premature infants because it is the least intrusive of the imaging techniques, although it is not as successful as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging capturing subtle changes in white matter—the type of brain tissue that is damaged in CP.

Evaluation

Doctors will order a series of tests to evaluate the child's motor skills. During regular visits, the doctor will monitor the child's development, growth, muscle tone, age-appropriate motor control, hearing, and vision, posture, and coordination in order to rule out other disorders that could cause similar symptoms. Although symptoms may change over time, CP is non-progressive. If a child is continuously losing motor skills, the problem more likely is a condition other than CP - such as genetic or muscle disease, metabolism disorder, or tumors in the nervous system.

Lab tests can identify other conditions that may cause symptoms similar to those associated with CP. Because many children with CP may also have related developmental conditions such as intellectual disability; seizures; or vision, hearing or speech problems, it is important to evaluate the child to find these co-morbidities as well.